Dear Arnold Schwarzenegger, Actor,

There’s a very simple binary way to judge your latest post-Gubernatorial comeback flick, Sabotage. And it only takes about ten seconds:

- The opening shot of the film is perfectly representative of why it doesn’t work.

- The second shot perfectly represents why it should have worked.

Coming from director David Ayer – fresh from the (sort-of) success of his found-footage cop thriller, End of Watch – it makes sense that the film begins with a grainy video clip, hissing and popping, striated with static, colors bleeding bright. In it, a middle-aged woman is bound and tortured by a masked assailant. She begs for her life. Weeps. We hear noises: loud ripping sounds. It’s not exactly clear what these sounds are, but they make the woman scream even louder.

In this unpleasant manner we are introduced to the world of Sabotage: a sadomasochistic, obscene, hyper-violent, obnoxious, inhumane, dim-witted, turgid, and generally unpleasant place to spend an hour and forty minutes.

Of course, lots of films are unpleasant. Who would want to spend time in the nameless any-city of Seven, or the dilapidated farmhouse of Texas Chainsaw Massacre? Those films, however, used dark places and darker moods to create tension with the wants and desires of their characters. Sabotage, on the other hand, treats its moral and behavioral ugliness like a thrill.

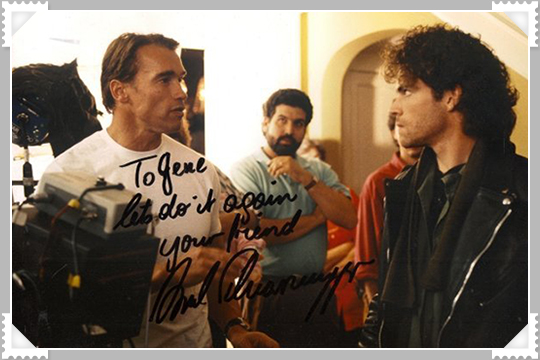

The second shot of the film is a close-up of you, Arnie. Slumped and swollen-eyed, looking worn-out in a way that we rarely see. Clearly you’re watching the grainy video clip, and clearly the woman being tortured means something to you. The shot doesn’t last long, but quickly establishes that isn’t the usual wisecracking, invincible Schwarzenegger hero we’ve come to expect after four decades. The knock on you has always been a lack of range, but that’s less about your acting abilities than it is about your career choices (you haven’t popped up in a lot of Paul Thomas Anderson flicks). Working with Ayer seems like a bold choice for you. His films are abrasive and kinetic in a different style than many of your past collaborators. If there was ever a chance for you to do something different – to redefine the Arnold mythos for a new generation – this would seem to be it.

But, alas, the ugliness representative in that first shot is too overwhelming.

Sabotage can’t seem to decide whether it’s a genre film or something different. Despite what is implied by that second shot, it turns out that you are, more or less, that wisecracking, invincible Schwarzenegger we know so well (though the wisecracks are a bit more filthy and the invincibility a bit less easy to believe). There’s even a scene where the grumpy chief pulls your badge and gun out of his desk drawer and puts you back on the case. But soon after there’s a sequence in which your arrival at a crime scene is intercut with the crime being committed – a sort of Silence of the Lambs-style misdirect – which gives us a sense that the film thinks a little too much of itself. Which is a shame, because Ayers has assembled a rather impressive all-star cast of shoulda-beens, briefly-wases, and almost-ares, including Olivia Williams, Harrold Perrineau, Terrence Howard, and Sam Worthington looking like the bassist from a Korn cover band.

You’re no stranger to these kinds of squandered opportunities, are you? I sat down a few weeks ago to fill in one of my biggest blind spots in the Schwarzenegger filmography, Last Action Hero, and even that magical convening of some of my favorite filmic elements (you, John McTiernan, parody,1990s action excess) somehow resulted in a thing that was far less than the sum of its parts. Just like Sabotage.

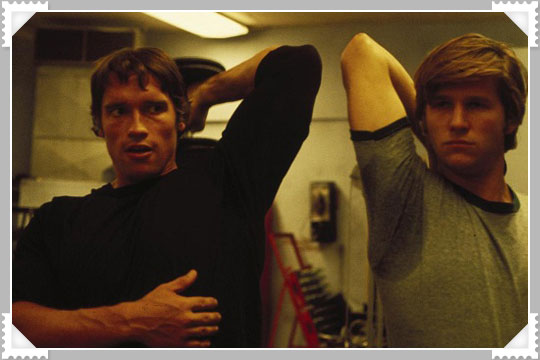

Yes, it seems that your long career has finally caught up to the obscene action movie aesthetic of modern times, and the result is kind of a bummer. I prefer you in your natural state: toting absurdly large machine guns, smirking to let us know that you’re in on the joke.

Sincerely,

Jared Young

Status: Return to Sender (1.5/5)